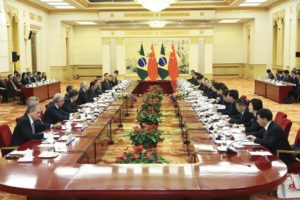

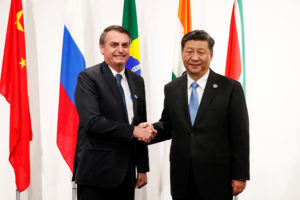

Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro begins his first visit to president Xi Jinping’s China today, after a year of tension between the two countries.

Though Bolsonaro has expressed a preference for tighter relations with the US and concern over what he sees as China’s ‘predatory’ approach to the Brazilian economy, the Asian country is still Brazil’s biggest trading partner.

Yet in recent decades, the China-Brazil partnership has extended way beyond doing business. The two countries signed a number of treaties and cooperation agreements that lent more political weight to the developing world, both bilaterally and in fora such as the BRICS group, which also contains with Russia, India and South Africa, and in international climate negotiations.

Cooperation on the environment has become an important element of diplomatic relations. As the home of the largest part of the Amazon, Brazil was a natural leader on environmental issues. And China, in its struggle to respond to the human, social and economic costs of its environmental crisis, began to prioritise the issue.

Now, with Bolsonaro’s Brazil dismantling environmental protections and the multilateral order fragmenting, we look at the history of cooperation on environment and its hope for the future.

Important agreements

Brazil and China began cooperating on space research in 1988. Ten years later, the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite, or CBERs, launched its first satellite.

Since its creation, the programme allowed Brazil to make great strides in monitoring deforestation — especially in the Amazon — via five satellites. The sixth will be launched by the end of the year.

2009

the year the BASIC group of emerging economies formed within climate negotiations

Twenty years later, in 2009, Brazil and China — along with South Africa and India — aligned in international climate negotiations and formed the BASIC group, which became an important forum to coordinate emerging economies’ position in the global struggle to fight climate change.

Former environment minister Izabella Teixeira told Diálogo Chino that China and Brazil became more closely aligned in 2015, when the two countries signed a bilateral statement on climate change.

The New Development Bank, created by the BRICS group, also pledged to support sustainable development in member countries.

Have they worked?

CBERs satellites helped Brazilian environmental protection agencies curb deforestation and bring it to record-low levels in the early 2010’s. However, today environmental agencies are reeling from budget cuts and the federal government is promoting an economic development model led by profit-seeking enterprises that is not consistent with environmental protection.

All the same, satellite data on deforestation has helped inform the public about the level of deforestation and it has responded with outrage to government inaction in enforcing environmental laws and regulations.

Brazil and China accepted they have responsibility too. This was an important change for the Paris Agreement to go forward

As for the BASIC group, it helped create consensus among developing nations that was crucial for getting the Paris Agreement on climate change over the line in 2015.

“The classic position by Brazil and China, developing countries, was that global warming was rich countries’ fault,” said Maurício Santoro, an international relations professor at the State University of Rio de Janeiro.

“Then Brazil and China accepted they have responsibility too. This was an important change for the Paris Agreement to go forward.”

Meanwhile, the NDB has proven slow to act as a driver of ‘green’ growth and has yet to prove it’s following its mission since the bank has refused to rule out investing in fossil fuels.

What can we expect from Bolsonaro’s China visit?

While countries often use state visits to sign important agreements, it is unclear whether Bolsonaro and Xi have any on the table. Brazil’s environmental minister Ricardo Salles will not travel to China, which makes it unlikely that the history of environmental cooperation will be strengthened.

“There is a lot of potential for cooperation,” said former environmental minister Izabella Teixeira, who worked closely with China during her tenure, which ended in 2016. “But the Brazilian government’s intentions and propositions in straightening bilateral relations on environmental issues aren’t clear.”

According to Teixeira, one of the main issues is the creation of a group to discuss environmental issues at the High-Level China–Brazil Cooperation and Concertation Commission, or Cosban, as it’s known in Portuguese.

Cosban is the highest-level permanent mechanism between the Governments of Brazil and China and has sub-committees on environmentally sensitive sectors including agriculture, energy and mining. But there are no indications that it will meet on this occasion.

Teixeira says this doesn’t mean certain sectors can’t collaborate. For example, there are demands on China that it take a stronger stance on the impacts of its soy and beef supply chains in Brazil. Both have been tied to deforestation. China’s largest food trading company Cofco has already shown willingness to cooperate on this issue.

However, as Bolsonaro’s grip on power has strengthened and international indignation at the Amazon fires raged, China has officially retained a quiet stance of non-interference towards the country, downplaying links between cattle ranching and deforestation and declaring support for Brazil’s efforts in tackling the blazes.